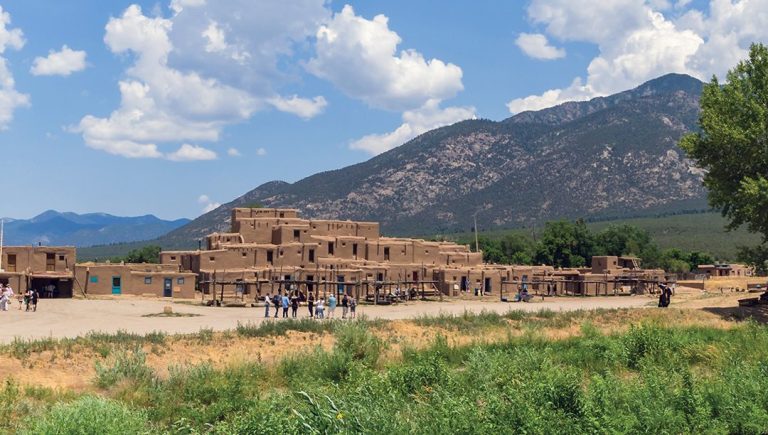

Visiting Taos Pueblo in New Mexico

Even if you’ve been in New Mexico for a while and think you’re inured to adobe, Taos Pueblo is an amazing sight. Two clusters of multistory mud-brick buildings make up the core of this village, which claims, along with Acoma Pueblo, to be the oldest continually inhabited community in the United States. The current buildings, annually repaired and recoated with mud, are from the 1200s, though it’s possible that all their constituent parts have been fully replaced several times since then.

About 150 people (out of the 1,200 or so total Taos reservation residents) live here year-round. These people, along with the town’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, have kept the place remarkably as it was in the pre-Columbian era, save for the use of adobe bricks (as opposed to clay and stone), which were introduced by the Spanish, as the main structural material. The apartment-like homes, stacked up at various levels and reached by wood ladders, have no electricity or running water, though some use propane gas for heat and light.

As you explore, be careful not to intrude on private space: Enter only buildings that are clearly marked as shops, and stay clear of the ceremonial kiva areas on the east side of each complex. These round structures form the ritual heart of the pueblo, a secret space within an already private culture.

You’re welcome to wander around and enter any of the craft shops and galleries that are open—a good opportunity to see inside the earthen structures and to buy some of the distinctive Taos pottery, which is only very lightly decorated but glimmers with mica from the clay of this area. These pots are also renowned for cooking beans. On your way out of the pueblo, you may want to stop in at the Oo-oonah Art Center (575/779-3486, 1pm-5pm daily Oct.-Apr.), where the gallery displays the work of pueblo children and adults enrolled in its craft classes.

San Geronimo Church

The path from the Taos Pueblo admission gate leads directly to the central plaza, a broad expanse between Red Willow Creek (source of the community’s drinking water, flowing from sacred Blue Lake higher in the mountains) and San Geronimo Church. The latter, built in 1850, is perhaps the newest structure in the village, a replacement for the first mission the Spanish built, in 1619, using forced Indian labor. The Virgin Mary presides over the room roofed with heavy wood beams; her clothes change with every season, a nod to her dual role as the Earth Mother. (Taking photos is strictly forbidden inside the church at all times and, as at all pueblos, at dances as well.)

The older church, to the north behind the houses, is now a cemetery—fitting, given its tragic destruction. It was first torn down during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680; the Spanish rebuilt it about 20 years later. In 1847 it was again attacked, this time by U.S. troops sent in to quell the rebellion against the new government, in retaliation for the murder of Governor Charles Bent. The counterattack brutally outweighed what had sparked it. More than 100 pueblo residents, including women and children, had taken refuge inside the church when the soldiers bombarded and set fire to it, killing everyone inside and gutting the building. Since then, the bell tower has been restored, but the graves have simply intermingled with the ruined walls and piles of dissolved adobe mud. All of the crosses—from old carved wood to new finished stone—face sacred Taos Mountain.