Death Valley’s Five Strangest Places

With a name like Death Valley, you might think that strange places abound, and you would be right. Salt flats, stark mountains, ancient lakes, and rugged rock formations make it a landscape that is often described as haunting and otherworldly. It’s also vast—large enough for visionaries, seekers of solitude, fringe miners, offbeat artists, or rescuers of haunted hotels to claim a piece of it and build the unconventional life of a desert-dweller, ignoring city and society.

Amidst the barbed desert expanses, lonesome stretches of highway, twisting dirt roads, and eternal quiet, life (and possibly even death) seems to take on a different shape. From creepy to beautiful, mysterious to moving, ridiculous to sublime, here are five of the strangest places I have come across in my desert rambles.

Tonopah Cemetery and the Clown Motel

The historic cemetery of Tonopah, Nevada, is a homespun monument to the pioneers of this hardscrabble mining town. Perfectly weathered wood tombstones dot the packed dirt. Shiny pennies are wedged in the silvery timber, a gesture from visitors wishing safe passage to the other side—i.e., “Please don’t haunt us.” According to the historical society’s entrance sign, this is the first Tonopah Cemetery, used from 1901-1911. Those ten years were clearly tough—here lie the 14 victims of the Tonopah-Belmont Mine fire of February 23, 1911, and the victims of the 1902 “Tonopah Plague,” among others. To get the full effect, stop and take in the weather-beaten picket grave fences, the stone outlines of those laid to rest, the distant stark mountains, stripped mining landscape, sun-bleached trailers, and the Clown Motel next door.

Yes, directly adjacent to Tonopah’s historic miner’s cemetery, the obsessively themed roadside budget Clown Motel welcomes truckers, bikers, and other weary travelers with nerves of steel. It features a lobby stuffed with clown collectibles, clown-themed rooms, clown wall paintings, clowns on shelves, clown road signs, clown magazines, life-sized clowns, free coffee, RV parking, and satellite TV.

Amargosa Opera House and Hotel

In 1967, Marta Becket’s car broke down in the almost ghost town of Death Valley Junction. She fixed the car but never left. Instead, something compelled her to take over the abandoned Corkhill Hall, which was originally constructed by the Pacific Coast Borax Company in 1925 as a recreation hall for miners. By the time she stumbled across it, it was rotting away in this nearly forgotten gateway to Death Valley.

Marta reopened the hotel, painted murals, reopened the theater, and performed ballet, sometimes to no audience outside of the figures she had painted. She created a life of art and freedom. The catch? The Amargosa Opera House and Hotel has a serious reputation for being haunted.

Driving up, the hotel rises unexpectedly from the harsh, alkaline landscape, white on white. Inside the air feels perpetually chilly despite the regular 110-degree temperatures outside. The staff leave rooms open so the curious can wander through. It’s been featured in documentaries and on the Travel Channel’s Ghost Adventures. Murals peek out of cracked stucco corners and hallways—cherubs, a nun, a parrot on a chain perch, and Marta haunting the desert as a dancing spirit.

Room 24 is said to harbor the crying ghost of a child who drowned in a bathtub in 1967. Room 32 is known for a malevolent presence. In Room 9, the most haunted, a presence holds down guests’ legs and feet and turns the doorknob. A section known as “Spooky Hollow,” once the miner’s dormitory, hospital, and morgue, was never reopened. Spooky Hollow is blocked off to all visitors, and the staff won’t talk about it.

It’s a marvel of human mettle that Marta Becket carved out her vision here in this far-flung and inhospitable place, that she breathed new life into the decaying hotel. Or maybe she kicked up the dust of a life that had never quite expired.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Burro Schmidt Tunnel

What prompts a man to hand-dig a tunnel through solid granite in the middle of the Mojave Desert every day for 32 years? The mystery may have been lost with William “Burro” Schmidt. He didn’t keep a journal or close friends; his only record is the nearly half-mile tunnel he dug using only a pick, a four-pound hammer and a hand drill. He carried the broken rock out in canvas bags, then wheelbarrow, then mine car running on tracks he installed. The tunnel ends abruptly on a steep hillside overlooking a dry lakebed and the obsolete railroad tracks that originally inspired him.

He started the tunnel to connect train lines transporting ore, but in the 1920s a road from Last Chance Canyon to the railroad town of Mojave eliminated need for a tunnel. Burro kept digging. Rumors persist about a rich ore vein or gold strike, but it seems clear that at some point Burro Schmidt’s vision was the tunnel itself.

Why he carried on is up for debate, but ultimately he made a life of daily purpose in the harsh desert. At the end of 32 years, he had himself an excellently constructed tunnel with a light at both ends.

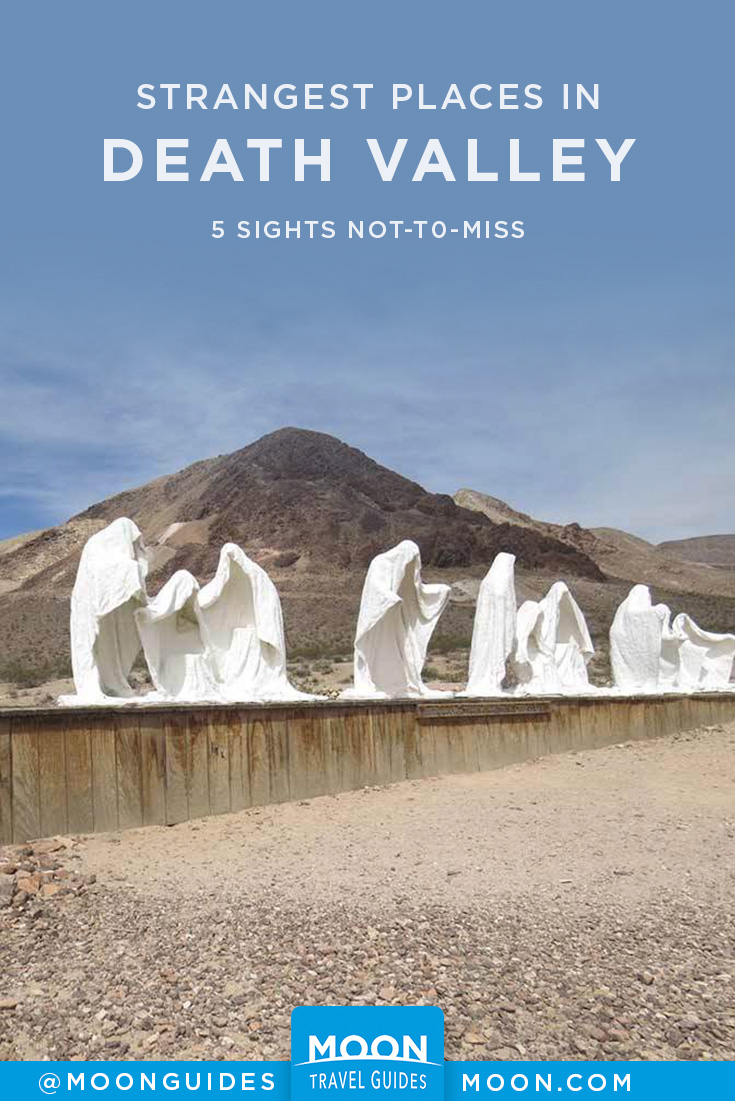

Goldwell Open Air Museum

Sometime in the 1980s, a group of Belgian artists got together and decided that the remote Nevada desert was a good spot for a large-scale sculpture installation. They chose the speckled Bullfrog Hills next to the ruins of the Rhyolite ghost town.

In the art park, life-size figures are flung across the stark desert. An oversized mosaic couch dwarfs anyone who attempts to sit on it. The abstract metal Tribute to Shorty Harris represents the life of the desert prospector with a pickaxe and a penguin. The most prominent piece is a rendition of Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous fresco, The Last Supper, where ghostly hollow figures huddle on a wooden platform. Nearby, eerie hooded shells hunch over bikes with flat tires and suggests that there is no escape. They look like they could flap open at any moment. Tourists treat them like photo cutouts at the state fair, taking selfies from under the empty hoods.

Trona Pinnacles

There is no way you would ever just end up out here. This ancient ghost lake, though, is worth a special detour. You can see the pinnacles on the long, dusty drive out, ghostly spires clustered on a vast dry lakebed like some miniature goblin village. As the forms come into clearer view you’ll see towers, tombstones, ridges, and cone shapes as high as 140 feet.

Located on the western side of Death Valley, the Searles Lake was once part of an interconnected chain of lakes stretching all the way from Mono Lake more than 200 miles north down to Death Valley. The Trona Pinnacles were formed underwater 10,000 to 100,000 years ago when calcium-rich groundwater met alkaline lake water. The result: alien tufa spires in a sea of stark desert.

You can see the mining town of Trona 13 miles away, huddled against the Argus Mountain Range, reflecting silvery sunlight. The intermittent belching boom of the mine rolls across the landscape, adding another surreal layer. Scan the far mountain ranges, and you can see where the water line used to be. It’s the only hint of water you’ll get.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Pin For Later