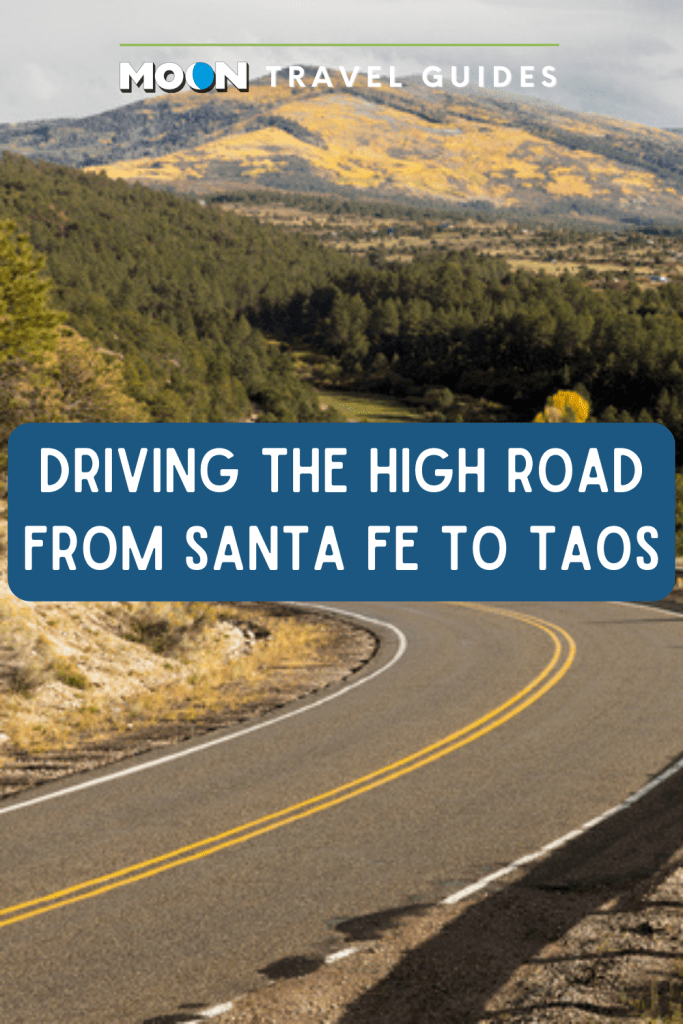

Taking the High Road from Santa Fe to Taos

Chimayó, Córdova, Truchas, Las Trampas, Peñasco—these are the tiny villages strung, like beads on a necklace, along the winding highway through the mountains to Taos. This is probably the area of New Mexico where Spanish heritage has been the least diluted—or at any rate relatively untouched by Anglo influence, for there has been a long history of exchange between the Spanish towns and the adjacent pueblos. The local dialect is distinctive, and residents can claim ancestors who settled the towns in the 18th century. The first families learned to survive in the harsh climate with a 90-day growing season, and much of the technology that worked then continues to work now; electricity was still scarce even in the 1970s, and adobe construction is common.

To casual visitors, these communities, closed off by geography, can seem a little insular, but pop in at the shops and galleries that have sprung up in a couple of the towns, and you’ll get a warm welcome. During the High Road Art Tour, over two weekends in late September, modern artists and more traditional craftspeople, famed particularly for their wood- carving skills and blanket weaving, open their home studios.

The route starts on Highway 503, heading east off U.S. 84/285 just north of Pojoaque.

Chimayó

From Nambé Pueblo, Highway 503 continues to a T-junction; make a hard left onto Highway 98 to descend into the valley of Chimayó, site of the largest mass pilgrimage in the United States. During Holy Week, the week before Easter, some 50,000 people arrive on foot, often bearing large crosses. At their journey’s end is a small church, seemingly existing in a time long since passed, that holds an undeniable pull.

Santuario de Chimayó

The pilgrimage tradition began in 1945, as a commemoration of the Bataan Death March, but the Santuario de Chimayó had a reputation as a miraculous spot from its start, in 1814. It began as a small chapel, built at the place where a local farmer, Bernardo Abeyta, is said to have dug up a glowing crucifix; the carved wood figure was placed on the altar. The building later fell into disrepair, but in 1929, the architect John Gaw Meem bought it, restored it, and added its sturdy metal roof; Meem then granted it back to the archdiocese in Santa Fe.

Unlike many of the older churches farther north, which are now seldom open, Chimayó is an active place of prayer, always busy with tourists as well as visitors seeking solace, with many side chapels and a busy gift shop. (Mass is said weekdays at 11am, Sun. at 10:30am and noon year-round.) The approach from the parking area passes chain-link fencing into which visitors have woven twigs to form crosses, each set of sticks representing a prayer. Outdoor pews made of split tree trunks accommodate overf low crowds, and a wheelchair ramp gives easy access to the church.

But the original adobe santuario seems untouched by modernity. The front wall of the dim main chapel is filled with an elaborately painted altar screen from the first half of the 19th century, the work of Molleno (nicknamed “the Chile Painter” because forms, especially robes, in his paintings often resemble red and green chiles). The vibrant colors seem to shimmer in the gloom, forming a sort of stage set for Abeyta’s crucifix, Nuestro Señor de las Esquípulas, as the centerpiece. Painted on the screen above the crucifix is the symbol of the Franciscans: a cross over which the arms of Christ and Saint Francis meet.

Most pilgrims make their way directly to the small, low-ceilinged antechamber that holds el pocito, the little hole where the glowing crucifix was allegedly first dug up. From this pit they scoop up a small portion of the exposed red earth, to apply to withered limbs and arthritic joints, or to eat in hopes of curing internal ailments. (The parish refreshes the well each year with new dirt, after it has been blessed by the priests.) The adjacent sacristy displays handwritten testimonials, prayers, and abandoned crutches; the figurine of Santo Niño de Atocha is also said to have been dug out of the holy ground here as well. (Santo Niño de Atocha has a dedicated chapel just down the road—the artwork here is modern, bordering on cutesy, but the back room, filled with baby shoes, is poignant.)

Chimayó Museum

The only other official sight in the village is the tiny Chimayó Museum, set on the old fortified plaza. It functions as a local archive and displays a neat collection of vintage photographs. Look for it behind Ortega’s Weaving Shop.

El Potrero Trading Post

Just to the left of the church, El Potrero Trading Post has been operating in some form for a century and, aside from its collection of santuario souvenirs and local art, is best known for its fresh green and red chile powders and piñon.

Rancho de Chimayó

The family-owned Rancho de Chimayó has earned a James Beard America’s Classics award for its great local food, such as sopaipilla relleno (fried bread stuffed with meat, beans, and rice), shrimp pesto green-chile enchiladas, and green-chile stew. Enjoy your meal on a beautiful terrace—or inside the old adobe home by the fireplace in wintertime. The place is also open for breakfast on weekends, and it rents seven rooms (from $79 s, $89 d) in an old farmhouse across the road.

Rancho Manzana

Beyond the Rancho de Chimayó’s hacienda, the surrounding area holds a few good options for staying overnight. Not far from the church, off County Road 98, Rancho Manzana has a rustic-chic feel, with excellent breakfasts, cozy casitas and much larger lofts. There’s a two-night minimum.

Casa Escondida

A couple of miles north of the church, Casa Escondida is a polished country hideaway with nine colorful Southwest-style rooms and a big backyard with lots of birdlife.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Córdova

Sabinita López Ortiz Studio

From Chimayó, turn right (east) on Highway 76 to begin the climb up the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Near the crest of the hill, about three miles along, a small sign points to Córdova, a village best known for its austere unpainted santos and bultos done by masters such as George López and José Dolores López. Another family member, Sabinita López Ortiz, sells her work and that of five other generations of wood-carvers.

Truchas

Highway 76 winds along to the little village of Truchas (Trout), founded in 1754 and still not much more than a long row of buildings set against the ridgeline. On the corner where the highway makes a hard left north is the village morada, the meeting place of the local Penitente brotherhood.

Nuestra Señora del Rosario de las Truchas Church

37 County Rd. 75; 505/351-4360

Head straight down the smaller road to reach Nuestra Señora del Rosario de las Truchas Church, tucked into a small plaza off to the right of the main street. It’s open to visitors only during June-August—if you do have a chance to look inside the dim, thick-walled mission that dates back to the early 19th century, you’ll see precious examples of local wood carving. Though many of the more delicate ones have been moved to a museum for preservation, those remaining display an essential New Mexican style—the sort of “primitive” thing that Bishop Lamy of Santa Fe hated. They’re preserved today because Truchas residents hid them at home during the late 19th century. Santa Lucia, with her eyeballs in her hand, graces the altar, and a finely wrought crucifix hangs to the right, clad in a skirt because the legs have broken off.

Cardona-Hine Gallery

Truchas has a surprisingly strong—albeit small—gallery scene. A standout is the Cardona-Hine Gallery, which showcases the paintings of the late Alvaro Cardona-Hine and Barbara McCauley.

Las Trampas

San José de Gracia Church

Farther north on Highway 76, the village of Las Trampas was settled in 1751, and its showpiece, San José de Gracia Church, was built nine years later. It remains one of the finest examples of New Mexican village church architecture. Its thick adobe walls are balanced by vertical bell towers; inside, the clerestory at the front of the church—a typical design—lets light in to shine down on the altar, which was carved and painted in the late 1700s. Other paradigmatic elements include the atrio, or small plaza, between the low adobe boundary wall and the church itself, utilized as a cemetery, and the dark narthex where you enter, confined by the choir loft above, but serving only to emphasize the sense of light and space created in the rest of the church by the clerestory and the small windows near the viga ceiling.

As you leave the town heading north, look to the right—you’ll see a centuries-old acequia that has been channeled through a log flume to cross a small arroyo.

Picurís Pueblo

One of the smallest pueblos in New Mexico, Picurís is also one of the few Rio Grande pueblos that has not built a casino. Instead, it capitalizes on its beautiful natural setting, a lush valley where bison roam and aspen leaves rustle. You can picnic here and fish in small but well-stocked Tu-Tah Lake. The San Lorenzo de Picurís Church looks old, but it was in fact rebuilt by hand in 1989, following the original 1776 design, a process that took eight years; it underwent a restoration that lasted several years. As at Nambé, local traditions have melded with those of the surrounding villages, and the Hispano-Indian Matachines dances are well attended on Christmas Eve. Start at the visitors center to pick up maps and pay a suggested donation. The pueblo is a short detour from the high road proper: At the junction with Highway 75, turn west, then follow signs off the main road for about 0.75 miles.

Peñasco

Sugar Nymphs Bistro

Peñasco is best known to tourists as the home of Sugar Nymphs Bistro, a place with “country atmosphere and city cuisine,” where you can get treats such as grilled vegetable tacos, green-chile cheeseburgers, grilled trout, and staggering wedges of triple-layered chocolate cake. In winter, hours are more limited, so call ahead.

Peñasco Theatre

The adjoining Peñasco Theatre hosts quirky music and theatrical performances as well as a number of youth workshops and classes June-September.

Pecos Wilderness Area

This is also the northern gateway to the Pecos Wilderness Area. Follow Highway 73 south out of Peñasco, and then after 3.7 miles turn left on Santa Barbara R Road, which turns into Forest Road 116, eventually ending after a further 5.9 miles at Santa Barbara Campground (sites $20), along the Rio Santa Barbara. The north end of the campground is the departure point for the West Fork Santa Barbara Trail to Truchas Peak, a scenic and occasionally arduous 25-mile round-trip hike that passes by No Fish Lake at over 11,500 feet in elevation. Contact the Española ranger district office (1710 N. Riverside Dr.; 505/753-7331; 8am-4:30pm Mon.-Fri.) or the one in the town of Pecos (Hwy. 63; 505/757- 6121; 8am-4:30pm Mon.-Fri.) for trail conditions before you hike.

Sipapu

Detouring right (east) along Highway 518, you reach Sipapu, an unassuming, inexpensive ski resort—really, just a handful of campsites ($35), suites (from $195), and casitas (from $135), plus an adobe house (from $259), at the base of a 9,255-foot mountain. Cheap lift tickets (from $29 full-day lift ticket) and utter quiet make this a bargain getaway.

Pot Creek Cultural Site

Returning to the junction, continue on to Taos via Highway 518, which soon descends into a valley and passes Pot Creek Cultural Site, a worthwhile diversion for its one-mile loop trail through Ancestral Puebloan ruins from around AD 1200. At its height, it’s believed the site was once home to up to 1,000 Ancestral Puebloans.

You arrive in Taos at its southern end— really, in Ranchos de Taos, just north of the San Francisco de Asis Church on Highway 68. Turn left to see the church, or turn right to head up to the town plaza and to Taos Pueblo.

Getting There

From downtown Santa Fe, the high road to Taos is about 90 miles. Follow U.S. 84/285 north for 17 miles to Pojoaque. Turn right (east) on Highway 503, following signs for Nambé Pueblo; turn left where signed, onto County Road 98, to Chimayó, then left again on Highway 76. In about 30 miles, make a hard left onto Highway 518, and in 16 miles, you’ll arrive in Ranchos de Taos, just north of the church and about 3 miles south of the main Taos plaza. The drive straight through takes a little more than two hours; leave time to dawdle at churches and galleries, take a hike, or have lunch along the way.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Pin It for Later