Take a Walk Through History on Boston’s Black Heritage Trail

Most visitors and Boston locals have walked the Freedom Trail, but not everyone realizes there is a similar historic trail through the heart of the city, marking key landmarks in Black history. The 1.6-mile Black Heritage Trail winds through Beacon Hill, connecting 15 sites associated with the Black community who fought for equal rights and emancipation leading up to, during, and after the Civil War.

Enslaved Africans were brought to Boston in 1638, but the American Revolution, during which many enslaved people fought on behalf of the colonies, was a turning point for the Abolitionist Movement in Massachusetts. After the war, the movement accelerated thanks to the determined efforts of the free African American community in Boston, and in 1790, Massachusetts became the only U.S. state to have no record of enslaved people during the first national census.

Between 1800 and 1900, most Black people who lived in Boston resided in what was known as the North Slope of Beacon Hill, which is where the Black Heritage Trail begins.

If you opt for the self-guided tour, start your walk at 46 Joy Street, about two minutes northwest of the Massachusetts State House. This official start of the trail, formerly the Abiel Smith School, is now home to the Museum of African American History (46 Joy St., 617/725-0022, $10 admission). But it began as the first building in the U.S. purposely built for educating Black children. It was named for Abiel Smith, who left a $4,000 endowment to the city for such an educational purpose. The school finally closed in 1855 after Black children were allowed to attend whatever school was closest to their own homes instead.

Behind the schoolhouse (and also part of the museum) is the African Meeting House (8 Smith Ct.), nicknamed the Black Faneuil Hall for its reputation for community organizing and hosting many great speeches during the Abolitionist Movement. Frederick Douglass spoke here in 1860, passionately expressing the need for free speech. In 1863, the meeting house became the site where African American soldiers volunteered to fight in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment lead by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

The next three stops were homes of Black residents during the 19th century. (Note: all the residences on the trail are currently inhabited by private citizens, so you cannot go inside.) Just across the narrow alley from the African Meeting House are the six wood-paneled Smith Court Residences. Farther along the trail on Phillips Street are John Coburn House (2 Phillips St.) and Lewis and Harriet Hayden House (66 Phillips St.). John Coburn House was home to John Coburn, a local businessman who was also the treasurer of the New England Freedom Association, which provided help to enslaved people seeking freedom. The Lewis and Harriett Hayden House was home to Black abolitionists Lewis and Harriet Hayden, who escaped enslavement in Kentucky. Their home was a key “station” on the Underground Railroad network enslaved people used to escape from the South to freedom. The Haydens were also consulted by Harriett Beecher Stowe when she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

After the Hayden house, head west to Charles Street, the main commercial thoroughfare running through the neighborhood. The Charles Street Meeting House (70 Charles St.), a towering red-brick building, was originally built as a church, later becoming the first integrated church in Boston before transitioning to a meeting house. Over the years, it has served as a safe haven for abolitionists, suffragettes, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Northeast of the Charles Street Meeting House is the John J. Smith House (86 Pinckney St.). John J. Smith owned a barbershop, which was a safe meeting place for abolitionists helping enslaved people along the Underground Railroad. Smith also served in the Civil War and was elected to the House of Representatives for three terms.

Continue east from John J. Smith House on Pinckney Street until you reach the intersection of Pinckney and Anderson. On the corner stands the beautiful Phillips School (65 Anderson St.), which became one of the first integrated schools in Boston in 1855 due to the tireless efforts of the Black community.

Farther down Pinckney Street is George Middleton House (5 Pinckney St.). Erected in 1797, this is the oldest existing, Black-built home on Beacon Hill. Owner George Middleton was a Revolutionary War veteran who led the all-Black “Bucks of America” militia in the war. Middleton was also a founder of the African Society, which helped lay the groundwork for the 19th-century Abolitionist Movement.

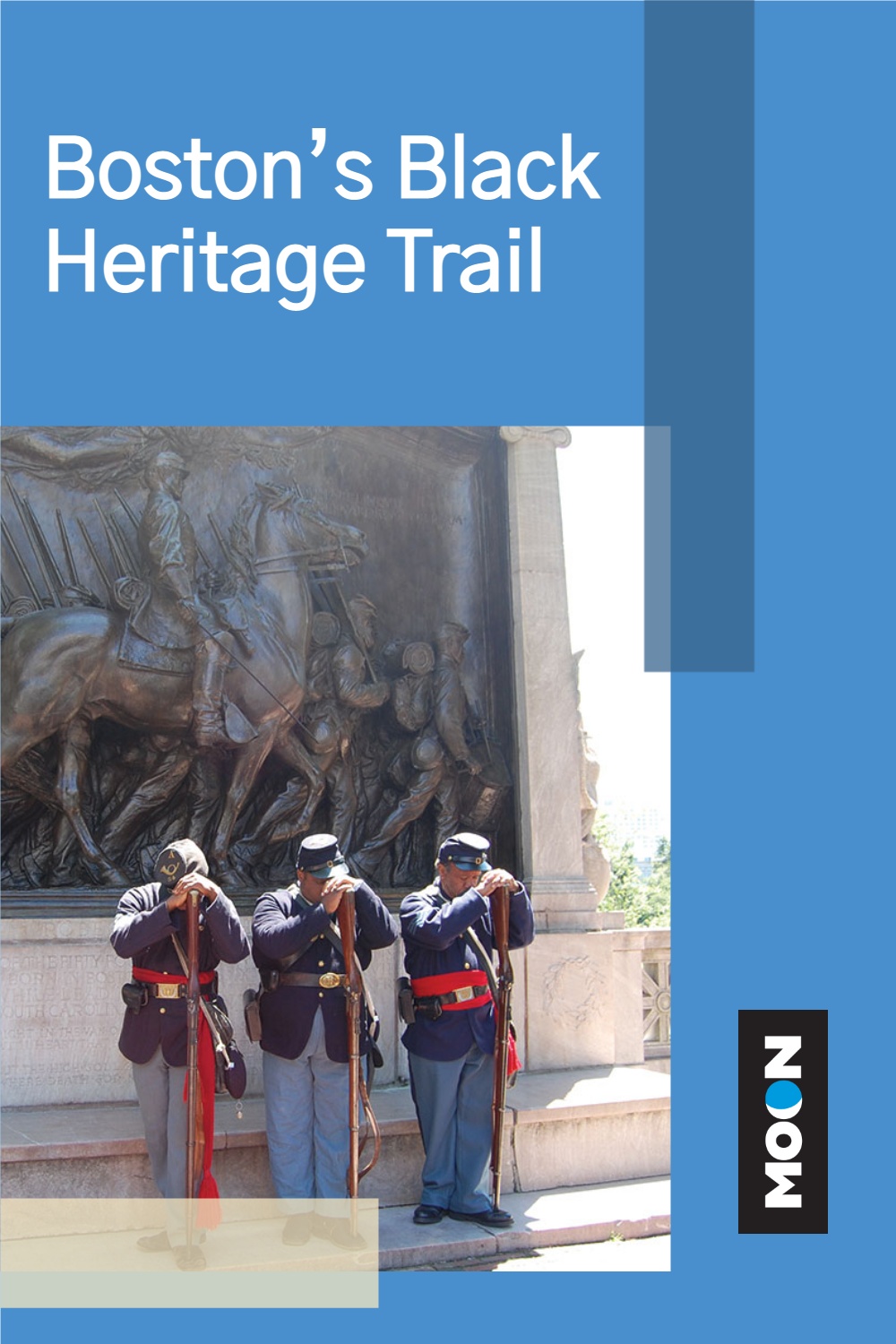

From George Middleton House, head south on Joy Street and then east on Beacon Street to reach the bronze Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Regiment Memorial (across from the State House at 24 Beacon St.), sculpted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The sculpture honors the African American volunteer infantry from the Revolutionary War, as well as its leader, mentioned earlier, Robert Gould Shaw. The regiment was made famous for its assault on Fort Wagner in an effort to capture the city of Charleston, South Carolina. While the regiment suffered a large loss of life (including Shaw’s) in the battle, their defeat inspired more Black soldiers to enlist in the army to help the Union.

Once you’ve reached the memorial, you’re at the end of the Black Heritage Trail, mere steps away from the busy Park Street and Downtown Crossing subway stations for convenient transportation to your next destination.

Timing: Self-guided tours of the trail are possible at all times of the year, with maps available at landmarks like the Abiel Smith School. If you prefer a guided tour, the National Park Service offers free 90-minute tours that start from the Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Regiment Memorial. These guided tours are operated in partnership with the nearby Museum of African American History and take place in spring, summer, and fall.

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next:

Pin it for Later