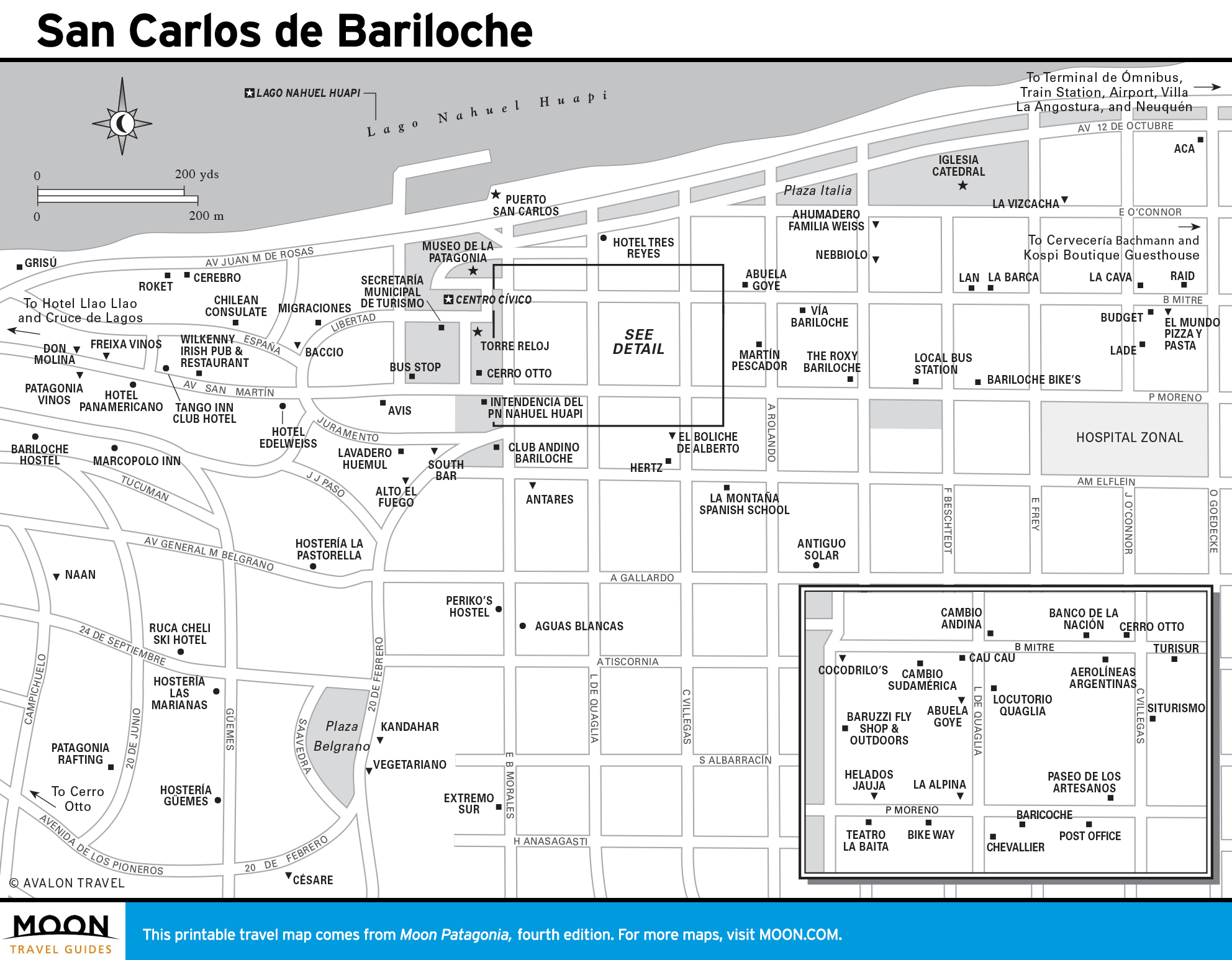

San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina

If Patagonia ever became independent, its logical capital might be Argentina’s San Carlos de Bariloche, the highest-profile destination in an area explorer Francisco P. Moreno called “this beautiful piece of Argentine Switzerland.” Bariloche, with its incomparable Nahuel Huapi setting, is the Lake District’s largest city, transportation hub, and gateway to Argentina’s first national park. Moreover, in the 1930s, the carved granite blocks and rough-hewn polished timbers of its landmark Centro Cívico set a promising precedent for harmonizing urban expansion with wilder surroundings.

Dating from 1902, Bariloche was slow to grow. When former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt visited in 1913, he observed:

Bariloche is a real frontier village. . . . It was like one of our frontier towns in the old-time West as regards the diversity in ethnic type and nationality among the citizens. The little houses stood well away from one another on the broad, rough, faintly marked streets.

When Roosevelt crossed the Andes from Chile, Bariloche was more than 400 kilometers from the nearest railroad, but it boomed after completion of the Ferrocarril Roca’s southern branch in 1934. Its rustically sophisticated style has spread throughout the region—even to phone booths. Unrelenting growth, promoted by unscrupulous politicians and developers, has detracted from its Euro-Andean charm. For much of the day, for instance, the Bariloche Center, a multistory monstrosity authorized by the brief and irregular repeal of height-limit legislation, overshadows the Centro Cívico.

As the population has grown from near 50,000 in 1980 to over 110,000 in 2010, its microcentro has become a clutter of chocolate shops, hotels, and timeshares and is notorious for high-school graduation bashes that leave hotel rooms in ruins. Student tourism is declining, in relative terms at least, but Bariloche still lags behind aspirations that were once higher than Cerro Catedral’s ski areas. Like other Patagonian destinations, it booms in the summer months of December, January, and February.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Bariloche holds a unique place in Argentine cinema as the location for Emilio Vieyra’s Sangre de Vírgenes (Blood of the Virgins), a Hammer-style vampire flick that was ahead of its time when shot in 1967 (it’s available on DVD). Perhaps Vieyra envisaged the unsavory things to come, but Bariloche’s bloodsuckers are only part of the story. The city and its surroundings still have much to offer, and at reasonable cost. Many of the best accommodations, restaurants, and other services lie along or near Avenida Bustillo between Bariloche proper and Llao Llao, about 25 kilometers west.

Sights in Bariloche’s Centro Cívico

Even with the kitsch merchants who pervade the plaza with Siberian huskies and St. Bernards for photographic poses, and the graffiti defacing General Roca’s equestrian statue, the array of buildings that border it would be the pride of many cities around the globe. The view to Lago Nahuel Huapi is a bonus, even when the boxy Bariloche Center blocks the sun.

The Centro Cívico was a team effort, envisioned by architect Ernesto de Estrada in 1936 and executed under APN director Exequiel Bustillo until its inauguration in 1940. When the municipal Torre Reloj (Clock Tower) sounds at noon, figures from Patagonian history appear to mark the hour. The former Correo (post office, but now the tourism office) is one of several buildings of interest, with steep-pitched roofs and arched arcades that offer shelter from inclement weather.

At the Centro Cívico’s northeast corner, Museo de la Patagonia Francisco P. Moreno (Centro Cívico s/n, tel. 0294/442-2309, 10am-12:30pm and 2pm-7pm Tues.-Fri., 10am-5pm Sat., from US$1.25) attempts to place the region (and more) in ecological, cultural, and historical context. Its multiple halls touch on natural history through taxidermy (better than most of its kind); insects (inexplicably including subtropical Iguazú); Patagonia’s population from antiquity to the present; the aboriginal Mapuche, Tehuelche, and Fuegian peoples; caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas; the “Conquista del Desierto” that displaced the indigenous people; and Bariloche’s own urban development. There is even material on Stanford geologist Bailey Willis, a visionary consultant who did the region’s first systematic surveys in the early 20th century.

Exequiel Bustillo’s brother, architect Alejandro Bustillo, designed the Intendencia del Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi (Nahuel Huapi National Park Headquarters, San Martín 24), one block north, to harmonize with the Centro Cívico. As a collective national monument, they represent Argentine Patagonia’s best.

Patagonia’s staggering landscapes, titanic glaciers, and rugged mountains evoke mystery and inspire self-discovery. Explore the ends of the earth with Moon Patagonia.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Pin it for Later